Traditional Fishermen Fear for the Future as Fibria S.A.’s Green Desert Suffocates Protected Mangroves

Green Desert – Eucalyptus monocultures, controlled by Fibria S.A., threaten the livelihoods of traditional fishermen in the Southern Bahia region, who are being criminalised for defending their territorial rights and the Cassurubá Extractive Reserve.

Green Desert – Eucalyptus monocultures, controlled by Fibria S.A., threaten the livelihoods of traditional fishermen in the Southern Bahia region, who are being criminalised for defending their territorial rights and the Cassurubá Extractive Reserve.

(Versão em português // Portuguese version: Pescadores tradicionais sufocados por deserto verde da Fibria S.A temem pelo futuro)

Report / images: Thomas Bauer / CPT Bahia

Editor: Elvis Marques / CPT Nacional

Translation: Raffaella Fryer-Moreira / University College London (UCL)

Their eyes shine when the oldest traditional fishermen speak of the richness of the mangrove swamps, which are part of the Banco dos Abrolhos, situated on the South Bahia coast. According to numerous studies, the region of Abrolhos presents the greatest marine biodiversity of the South Atlantic. The region of long coasts, where several rivers meet the sea, is notable for the elevated productivity of fish and seafood catches, due to the high quantity of nutrients in the rivers, the sea, and the vegetation on the margins of the estuary [the aquatic environment between river and sea].

The elders say that here they never lacked fish, crabs, prawns, oysters, among others. The astonishing abundance here offered families comfortable livelihoods, in an area that pioneered the occupation and settlement of Bahia and of Brazil. Decades ago, the region counted on a leafy Atlantic Forest, rich in biodiversity with innumerable endemic species which, over the years, principally after the inauguration of the BR-101 highway in 1973, from Vitória (Espirito Santo) to Salvador (Bahia), and the arrival of monocultures [initially papaya and, from 1980, eucalyptus], suffered significant impacts. In the South of Bahia, the county of Caravelas is also known worldwide because of the Abrolhos Archipelago, where whales can be seen which pass through the region every year.

Cassurubá Extractive Reserve amidst a sea of eucalyptus

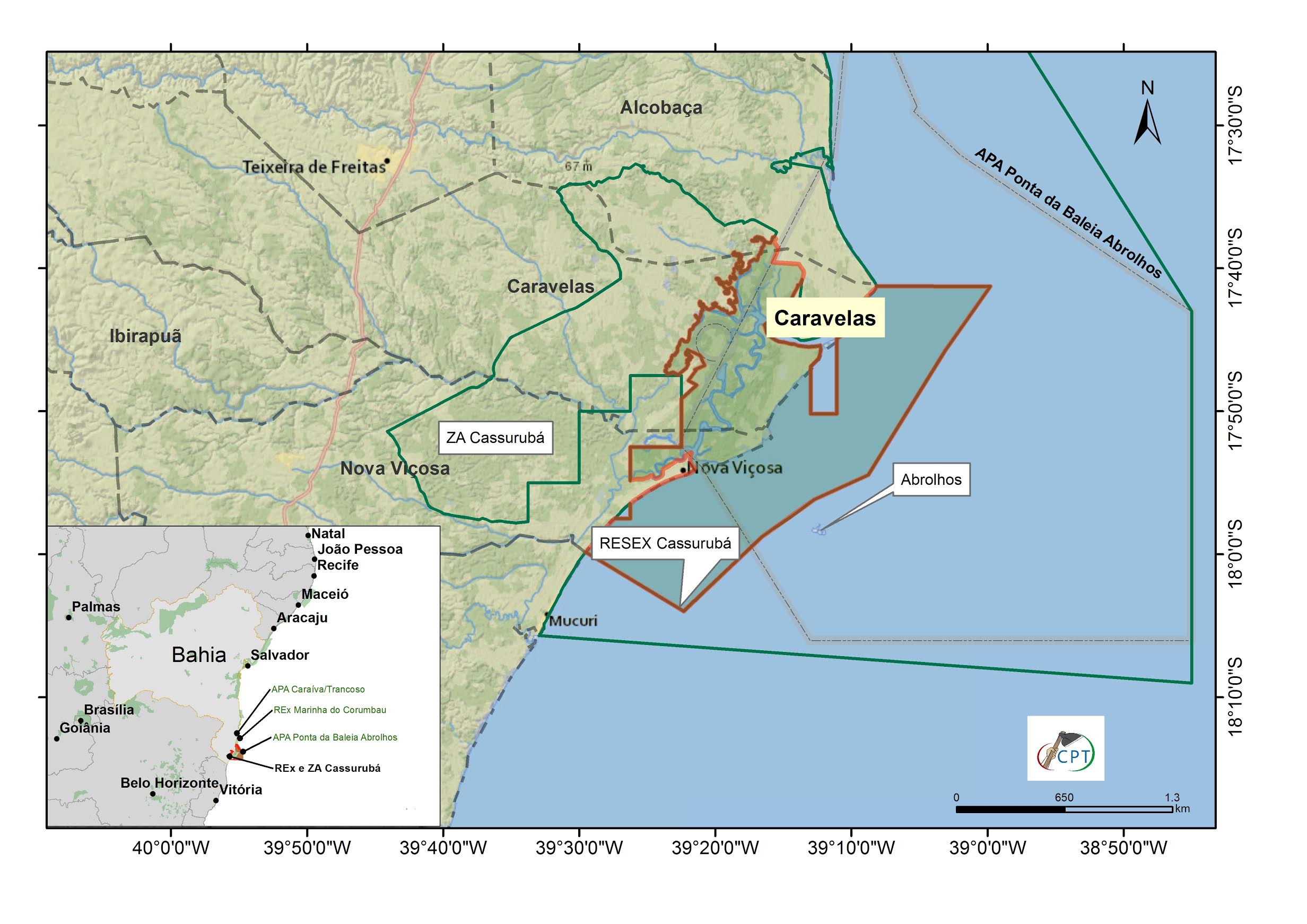

Environmental analyst from the Chico Mendes Institute of Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio) and currently director of the Cassurubá Extractive Reserve (RESEX), located in the county of Caravelas, Marcelo Lopes points out that the reserve was created in June 2009. Today, the area totals 100,687 hectares, and affects the counties of Alcobaça, Caravelas, and Nova Viçosa.

Calls to create the reserve were made by local fishermen and community members, following conflict with a private company which intended to install a prawn farm on public land, which threatened the livelihoods of the traditional fishing families. Diverse partnerships between the community and universities, public bodies, NGOs, among others, contributed to the interruption of this project and were decisive in the creation of the Extractive Reserve (RESEX) in the territory of the estuary and part of the corals of the Archipelago.

Created eight years ago, the group currently responsible for the management of the RESEX, coordinated by Marcelo Lopes, prioritise in their work the social organisation of local communities – the approximately 1,600 fishing families who live in Cassurubá. But the challenges are not confined to this region. When asked about the eucalyptus monocultures, which suffocate the mangrove swamps and the region which surrounds the RESEX, and the installation of a port terminal in 2002 belonging to the company Fibria S.A., Marcelo has a clear position. See the video below:

{youtube}https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RIfcagLBEg{/youtube}

Fibria S.A., founded in 2009, was constituted from the merger of two companies, Aracruz and Votorantim Cellulose and Paper, and is a Brazilian company with open capital and, today, is world leader in whitened cellulose. The company exports its product to more than 40 countries. The two largest share-holders are Votorantim S.A., which holds 29.16% of shares, and the National Development Bank (BNDES), with 29.02% of shares – in other words, the Brazilian government itself. These two groups define all the guidelines, politics, and directors of Fibria S.A., which still owns 43% of the shares in circulation (free float) sold on the financial market.

The company owns three factories in the state of Espírito Santo. Besides these, one factory is in construction in the state of Mato Grosso, and innumerable eucalyptus monocultures are being implemented in various regions of Brazil, including in the extreme south of Bahia, as in the case of Caravelas. 90% of the area of this county is occupied by the cultivation of eucalyptus, according to the city councillor Julinda Moraes, presented at a public hearing in 2014 in the city of Teixeira de Freitas, located around 80 kilometres from Caravelas, to discuss the impacts caused by the eucalyptus monocultures in the region. The article referring to this hearing was published in Agência Câmara.

The company owns three factories in the state of Espírito Santo. Besides these, one factory is in construction in the state of Mato Grosso, and innumerable eucalyptus monocultures are being implemented in various regions of Brazil, including in the extreme south of Bahia, as in the case of Caravelas. 90% of the area of this county is occupied by the cultivation of eucalyptus, according to the city councillor Julinda Moraes, presented at a public hearing in 2014 in the city of Teixeira de Freitas, located around 80 kilometres from Caravelas, to discuss the impacts caused by the eucalyptus monocultures in the region. The article referring to this hearing was published in Agência Câmara.

This company uses eucalyptus to produce a chemical paste with a cellulose base, a material commonly used in the production of paper. To put this in context, in Germany alone the consumption of paper (paper towels, disposable paper cups, white document paper, tissues, etc.) annually exceeds 235kg of paper per capita. In comparison, in Brazil the consumption per capita is 43kg of paper. In this sense, it is important to note that the consumers and investors of the countries which import the product are jointly responsible for this expansion, provoking serious environmental damage.

Violent processes of deterritorialisation

From the embankment in the airport of Teixeira de Freitas until the city of Caravelas, the profound process of deterritorialisation both on land as well as of those who work on the sea is truly astounding. The expansion of eucalyptus, which today occupies ancient rural areas, has provoked severe environmental impacts and, in many cases, serious territorial conflicts, resulting in deaths, such as the Quilombo [traditional communities of African descent] member Diogo Oliveira Flozina, 27 years old, father of two children, whose house was raided by three plainclothes police officers, which, according to witnesses, murdered the young man in his own home.

The families of the Quilombo community of Volta Miúda, situated in the Caravelas county, where Diogo lived, following the report from the Geledés portal (Institute of Black Women), believe that he was killed as a result of his opposition to producers of eucalyptus. The case occurred in 2011. “The Quilombo community of Volta Miúda is certified by Palmares, has 120 families in a sate of concerning poverty and struggle to survive as a result of the domination of eucalyptus companies. In the region, besides Volta Miúda, another 7 communities live in conflict with police and private companies, and these communities feel isolated, with no support or protection from public authorities”, says the Geledés report.

This report is but one among several others, such as the drying-up and contamination of the soil in the region, the disappearance of hundreds of streams and natural springs, the deforestation of the Atlantic Forest, the decline of family agriculture and the eviction of tens of thousands of people to large cities, as has been recently denounced in the Open Letter of the First Seminar of Community Strengthening of the Cassurubá RESEX, which occurred at the end of November 2017.

Besides these impacts, the fishermen point to the new port terminal and the dredging of the Tomba Canal, both in Caravelas, which negatively impact the mangrove swamps and the entire ecosystem of the RESEX Cassurubá. With the dredging, the canal – which before served only for the navigation of small boats during high tide – was widened and, in some areas, now reaches 20 metres in depth. This intervention by Fibria S.A. today guarantees the passage of large vessels, which each carry cargoes equivalent to 80 or 100 carts of eucalyptus trunks, day and night, independent of the tide level. Many vessels leave the port overloaded and, frequently, some trunks fall in the river and in the canal, which has resulted in serious accidents and damages among the traditional fishermen and their boats.

Frequently, some eucalyptus trunks fall in the river and canal, which has led to serious accidents.

The port terminal in the county of Caravelas, in the South of Bahia

Many fishermen suspect that the widening of the canal has also affected the food chain in the region and, consequently, the low productivity of fish stocks and seafood in the area. As the flux and strength of the water has increased considerably since the widening of the canal, every large tide covers the land and knocks down whatever it finds in its way, causing erosions, as can be seen in Barra Beach. Moreover, the force of the water removes many nutrients from the mangrove swamps, which before would be retained in the estuary and near the coast; also, the little that remains near the coast is affected again during the dredging process itself. During this process, all the material from the bottom of the sea is suspended by the dredge, then dispersed in the currents which take the nutrients far away. Such that, according to the oldest fishermen, it was never before possible to find prawns far from the coast, near the Island of Coroa Vermelha, which could indicate a that marine life has migrated to find food in more distant locations, and thus signals an alteration in the entire food chain.

Another visible impact, principally in the Island of Pontal do Sul, which is situated next to the mouth of the Tomba Canal, is the death of the mangroves. The material that is dredged (sediment) is discarded at the end of the canal, in the direction of the sea. The marine currents, in turn, return this sediment to the canal and the beaches, which has suffocated the mangroves, which can be observed on the island, which could disappear entirely in the near future.

Eight years ago an environmental survey was conducted by H.M. Project and Engineering Consultancy Ltd. and Aracruz Cellulose S.A., entitled “Dredging of Access to Tomba Canal in Caravelas/BA” (Relatório Técnico HM RT-007-08, 10 Volumes), which affirms that “the dredging activities in the marine environment of the region will not impact the reefs and corals, and only specific impacts are detected, of low magnitude and rapidly reversible, which do not result in permanent deleterious effects on the environment”. A statement which has been questioned following independent feedback from the Coalition SOS Abrolhos, which unites several organisations, NGOs, and universities. The document produced by this group regarding the environmental survey conducted by Aracruz Cellulose on the 23rd of April 2009 affirms that “it is indispensable that Aracruz Cellulose recognises and assumes the environmental and socioeconomic impacts of their operations in the county of Caravelas, so that from there we may initiate a technical discussion founded on alternatives for the mitigation and compensation of these impacts”.

Vessel belonging to Fibria S.A. as it enters the Tomba Canal, with dried mangroves.

In the face of serious denouncements presented by the local community and organisations, the Communications Advisors of the Fibria S.A. Company were invited to comment on the problem, however, until the publication of this article, no response has been received.

Fishermen in Protest

In the face of these impacts and the claims of fishermen which have been ignored by the Fibria S.A. Company, local traditional fishermen were left with no choice but to organise a protest on the 22nd and 23rd of July 2017, to draw the attention of the authorities. This was the second protest led by fishermen in 2017 – the first took place on the 1st of July. Fisherman Chanto speaks about the last mobilisation:

{youtube}https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RX48dvWfX7U{/youtube}

The peaceful protest lasted almost two days, but was interrupted by a judicial order conceded by a judge from the city of Teixeira de Freitas, who accused four fishermen and the autonomous movement of having violated the right of the company to move freely, as well as loss earnings, both in the embarkation area and in the factory in Aracruz. As the focus of the protest was the Fibria S.A. Company, the participants in the protest guarantee that the other accusation made by the judge, of having obstructed the canal and impeded the passage of other vessels, is simply untrue.

Fisherwoman Maria Braz, from the county of Alcobaça, who has lived in Caravelas for 40 years and knows the region like the palm of her hand, remembers the times of abundance. According to her, since the installation of Fibria S.A. Company in the region, many things had changed. “We aren’t in the wrong, protesting in the face of this disaster that is happening. It is our right. Every day our lives become more difficult”, she tells us.

{youtube}https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65UjcRp8Bjo{/youtube}

In truth, the fishing families did not expect and did not wish the tension between themselves and Fibria S.A. to reach this extreme. The fishermen see this criminalisation as a form of intimidation. However, knowing their rights, these fishermen affirm that even suffering this process of criminalisation they will not give up on the struggle for their territory and the community has awoken in the face of the loss of their land. For these fishing people, the company has shown yet again how little respect it holds for the families of traditional fishermen in their own territories. Together, these fishermen are conscious that to lose their traditional territory would mean the end of the local fishing tradition and their way of life, as well as the destruction of the mangrove swamps and its infinite biodiversity, which could occur as a result of the environmental damage already caused inside the Cassurubá Extractive Reserve and its surrounding region.